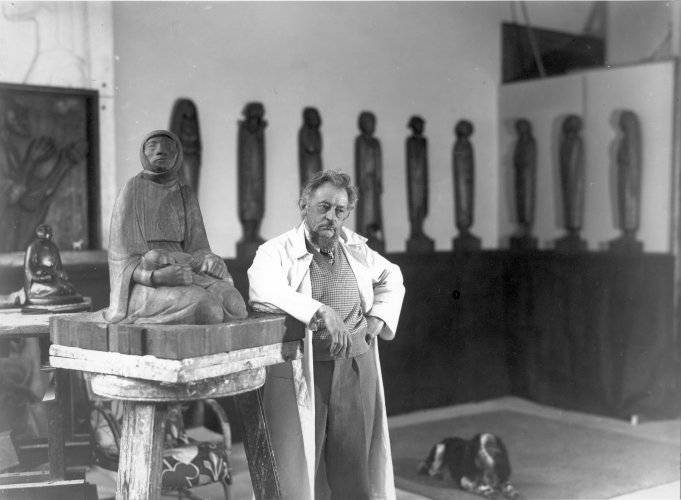

The work of the expressionist sculptor, draughtsman and writer Ernst Barlach (Wedel 1870–1938 Rostock) is complex and ambivalent. Barlach’s lifelong concern with the human figure combines the aspiration to timelessness with contemporary criticism, concrete observation with abstraction, an austere formal repertoire with vitality and a wealth of meaning.

“My work is labelled with terms such as 'cultic' and 'mystical', and people rack their brains to work out which riddle I am posing and the skill with which I make it difficult to solve. I believe that what cannot be expressed in words can be made accessible through form and can become the property of another. I need an object on which I can break my teeth to pieces.”

Ernst Barlach, 1932

Barlach’s path to expressionism led through the academic traditions of the 19th century and the creative ideas of naturalism, symbolism and art nouveau. In 1906 a journey to Russia gave him the decisive motivation for a radical simplification and monumentalisation of his visual imagery.

Through the reduced outer appearance of his figures, Barlach sought to comprehend elemental inner states. The interlinking of individual form with universal content, material limitations with freedom of thought and a rootedness in the here and now with a yearning for transcendence became the main theme of his art. Barlach’s attempts to create timelessly valid statements about the nature of human existence did not prevent him from taking a critical angle on the present – his art reflects social hardship and defies bourgeois conventions.

The First World War – which he initially welcomed as the beginning of a new era and then endured as the breakdown of Western civilisation – heightened Barlach’s scepticism towards conventional values and worldviews. He increasingly dedicated himself to key questions of faith while not committing himself to any particular confession. Barlach’s interest in what goes beyond the rational and tangible not only fuelled his sculptural and graphic production but also characterised his dramas, which are infused by idiosyncratic metaphors.

From 1927 onward Barlach designed several monumental works for public spaces. In his memorials for the victims of the First World War he found fundamentally new forms of collective commemoration. His demonstrative decision to forgo heroicism and unbroken pathos caused him to become the target of nationalist defamation campaigns; until his death in 1938 he was hounded by the National Socialists as a ‘degenerate’ artist. Despite being massively attacked, Barlach remained imperturbable: he publicly advocated freedom of thought and artistic expression, and persevered with his work. In radical opposition to the fascist ideology of ‘community’ he turned to address the existential loneliness of the individual. Marginal figures in society – the needy, the broken, the outcast – remained the focus of his art.

Following the end of the Second World War, Barlach was quickly rehabilitated in Germany. His oeuvre has long been regarded as an important contribution to 20th century art – and it still remains a challenge today.